Journal of the School of Art History

Academy of Art University

The papers in Alla Prima, written by students in the School of Art History BFA and MA programs, demonstrate the depth and breadth of the field, addressing artists and periods that span centuries and continents. Wide-ranging questions are asked regarding artistic inspiration, appropriation and influence, and showcase the rigorous caliber of the author’s scholarly work.

The first volume of Alla Prima was envisioned and constructed through the support of many. The editor is particularly grateful to Stephen P. Williams, Associate Editor of Alla Prima, for his tireless work on the journal, and to the Art History Student and Faculty Editing Boards who, together, shaped the very nature of this volume, and in doing so produced a beautifully varied compendium that shares but a small corner of our field.

Gabriela Sotomayor

Gabriela Sotomayor

Director, School of Art History

Academy of Art University

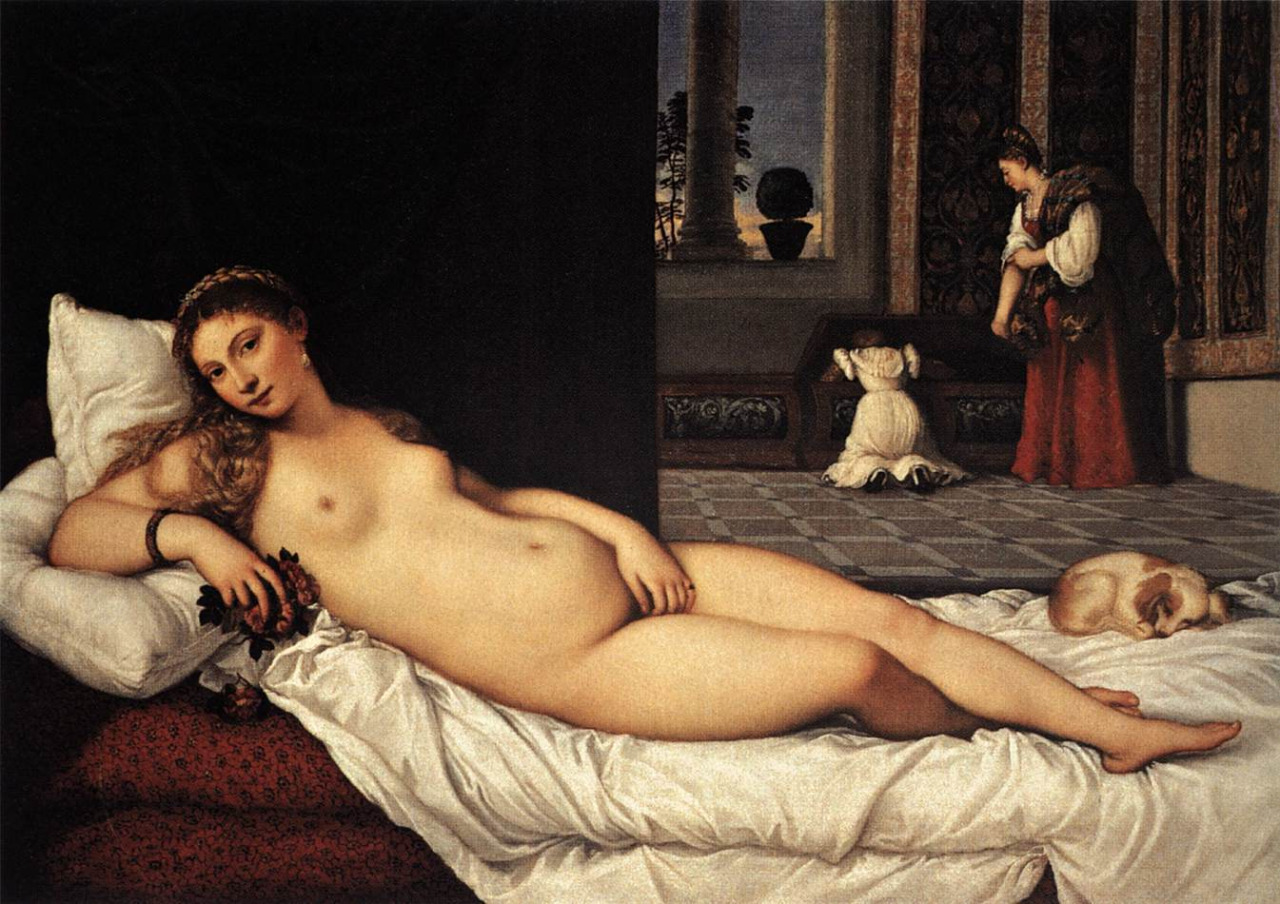

Venus of Urbino, Olympia, and the Presentation of the Female Nude

Heather DeToma

BFA Art History Student

ABSTRACT

Throughout history artistic trends, styles and movements come and go. However, as time advances it is easy to see how the past consistently influences the present. In viewing Titian’s Venus of Urbino, and Edouard Manet’s Olympia this phenomenon is clear. With hundreds of years between their creations, which embodies their respective movement’s unique stylistic characteristics, the two paintings mirror each other in subject and layout. The atmosphere of Renaissance Venice and nineteenth-century France were quite different and this general mood can also be seen through each artist’s work. Though viewers may immediately notice similarities between the paintings, their intent, purpose and message vary greatly. Both paintings were bold and unconventional in their time, but one is known for its scandal, and the other for reintroducing the female nude as an acceptable subject in painting. Read more >

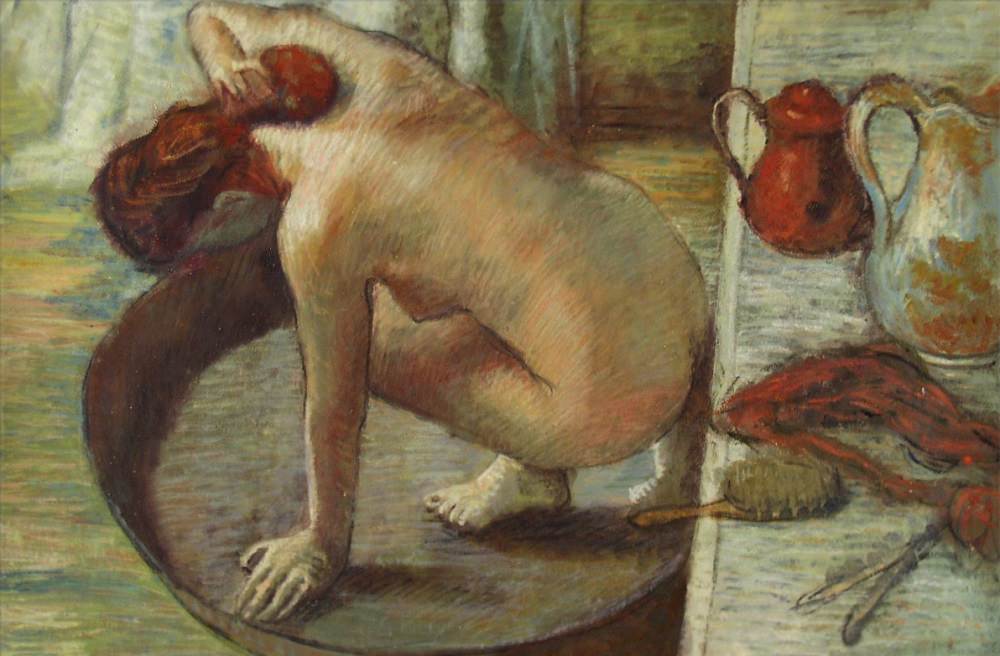

Women in the Water: How Edgar Degas's And Torii Kiyomitsu's Bathing Females Washed Over Artistic Traditions

Rhiannon Hilliard

BFA Art History Student

ABSTRACT

The female human form has long been the choice subject of many artists throughout the course of history. From marble, paint, or pencil, artists have conjured images of loveliness, and out of their souls, brought them into the world. However idealized a representation of a woman could be, figures of feminine beauty varied from culture to culture. What’s more, artistic revolutions brought forth new ways of depicting the female figure; beauty and idealistic notions of what a woman should be evolved. Throughout the artistic evolution of the female subject, artists often called upon inspirations from other cultures, working with a new perspective to capture their visions. In the utilization of these new perspectives, so too evolved the artists’ ideas of how to display the woman in their pieces; what should she do? How should she address the audience? Should she invite them into her world, or exclude them from it? For the French Impressionist artist Edgar Degas and the Japanese ukiyo-e artist Torii Kiyomitsu, answers to these questions could be found in the simple image of a woman in a bath tub. Although the techniques used by Degas and Kiyomitsu to create their women in the water differed, Degas most certainly drew inspiration from the work of artists like Kiyomitsu, among others practicing during the ukiyo-e period. Degas’ The Tub (1888) and Kiyomitsu’s Bathing (1750) depict intimate, fleeting moments of women during a bath. The comparison and contrast between the works express the relationship of Impressionist artists with ukiyo-e artists, as well as how their respective cultures viewed a female form and how two male artists defied a woman’s traditional roles in society through artistic representations. Read more >

Guarino Guarini: Architectural Influences And Characteristics

Marydarlene Cieszynski

MA Art History Student

ABSTRACT

Guarini wrote in Euclides Adauctus that “the incomparable magic and miracle of mathematics represents the true gifts that architecture holds.” It was through his understanding of that magic and miracle that he shared with the world the gifts he found in architecture. Guarino Guarini is considered the premier architect of Piedmontese Baroque. However, he was so much more than an architect. Guarini was an ordained Theatine Priest and recognized as a renowned theologian, philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer. Guarini’s lifelong pursuit of knowledge combined with his travels within Europe enabled him to merge and combine vastly different architectural vocabulary into a coherent and innovative style. His uses of Gothic and Islamic elements within 17th century applications were unique to his works. There are several scholars who have written considerably on Guarini’s life and works. This paper will examine Guarini’s biography, major architectural buildings, and the influences that enabled him to develop two stylistic characteristics. Read more >

Curiosities and Contradictions in the Iconography of Benozzo Gozzoli’s Procession of the Magi (1459-1461)

Laura L. Martin

MFA Art History Student

ABSTRACT

Benozzo Gozzoli’s fresco cycle, Procession of the Magi (1459-1461), is a perfect microcosm of the curiosities and contradictions that surround the artist’s career and oeuvre. Located in the in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in Florence, the fresco cycle covers three walls of the Medici’s private chapel in their grand palazzo. Existing art historical analysis of this fresco cycle does not fully identify or examine the many curiosities and contradictions that make Gozzoli’s Procession and the artist’s talent wholly unique, so in this paper I will examine one main area of contradiction: The origin of the iconography of the Procession of the Magi. Because there are no primary sources that outline the commission of Gozzoli’s Procession, scholars have put forth five incomplete and contradictory interpretations of its iconography that, collectively, do not fully describe its narrative and meaning: (1) the Council of Florence (1439); (2) Congress of Mantua (1459); (3) competition between Italy’s ruling families; (4) the interplay between power and piety; and (5) a text by Gentile Becchi (c. 1420-97). While these five interpretations offer valid and reasonable evidence that might, in part, explain the iconography of this fresco cycle, they are incomplete and leave too many unanswered questions related to the fresco cycle’s overall meaning. Read more >